Please direct questions to assessment@duke.edu

We thank the following individuals for their long-standing commitment to the practice of learning outcomes assessment at Duke, and for their active support of the initiatives and services described in this document.

- Valerie Ashby, Ph.D.

- Lee Baker, Ph.D.

- Frank Blalark, Ph.D.

- Jennifer Francis, Ph.D.

- Molly Goldwasser, Ed.D.

- Patricia Hull

- David Jamieson-Drake, Ph.D.

- Valerie Konczal

- Sally Kornbluth, Ph.D.

- Peter Lange, Ph.D.

- Shawn Miller

- Elise Mueller, Ph.D.

- Arlie Petters, Ph.D.

- Philip Pope

- Cheryl Ratchford

- Kendrick Tatum

- Robert Thompson, Ph.D.

- Lee Willard, Ph.D.

- Edward Gomes

Educators constantly are engaged in the practice of assessment and improvement, whether we’re aware of it or not. Every enhancement to a learning experience, inside the classroom and in the co-curriculum, is based on some explicit or implicit evaluation of the learning occurring (or not occurring) therein. Learning outcomes assessment is the continuous and systematic process by which (1) we collect evidence about students’ learning, (2) communicate these findings with students, colleagues, college leaders, accreditors, and the community at large, and (3) demonstrate to a variety of stakeholders that we use these findings to inform and improve educational practice. Executed well, it is a scholarly enterprise that utilizes a variety of research methodologies and is held to rigorous standards.[1]

Observers sometimes approach assessment narrowly, perhaps assuming that as long as data about students are collected, the requirements of assessment have been satisfied. And, yes, evidence is central to this enterprise! However, assessment as we practice it in Trinity College is the broader tradition of evaluating the degree to which our students know and can do the things we expect them to do, and then making conscious, evidence-based enhancements to our programs and practices. Thus, the four main purposes of program assessment are:

- To improve. The assessment process should cultivate recommendations for ways the faculty can enhance the program.

- To inform. The assessment process should inform faculty and other stakeholders of the program’s impact and influence.

- To prove. The assessment process should demonstrate to students, faculty, staff, and external observers the program’s strengths and opportunities for improvement.

- To support. The assessment process should provide support for campus decision-making activities such as program review and strategic planning, as well as external accountability (e.g., accreditation).

A common misconception about assessment is that it is driven and directed by external accreditors, who enforce uniformity of outcomes, measures, and standards in undergraduate education. On the contrary, our regional accreditor[2], as a partner in the process of assessment, encourages faculty autonomy in the development of learning outcomes and the methods by which they are studied. Likewise, the Office of University Assessment urges program faculty to develop relevant learning outcomes for students in that program. As disciplinary experts, you are in the best position to articulate these values and to establish an assessment methodology that makes sense for your program.

Another misconception about assessment is that assessment happens only occasionally. Program reviews[3] may occur on a 10-year cycle, but assessment – as a culture of iterative study of and reflections on student learning – is always underway. The Office of University Assessment supports this approach by encouraging regular meetings among assessment liaisons, offering workshops and information sessions throughout the academic year, and most importantly structuring your assessment report as a reflective portfolio. To be effective – that is, to use evidence productively – assessment must be continuous. As the program evolves, so too does its assessment plan and methods of measurement.

In 1992, the American Association of Higher Education published nine principles[4] of assessment, which remain relevant and influential thirty-some years later. These principles assert:

- The assessment of student learning begins with educational values.

- Assessment is most effective when it reflects an understanding of learning as multidimensional, integrated, and revealed in performance over time.

- Assessment works best when the programs it seeks to improve have clear, explicitly stated purposes.

- Assessment requires attention to outcomes but also equally to the experiences that lead to those outcomes.

- Assessment works best when it is ongoing, not episodic.

- Assessment fosters wider improvement when representatives from across the educational communities are involved.

- Assessment makes a difference when it begins with issues of use and illuminates questions that people really care about.

- Assessment is more likely to lead to improvement when it is part of a larger set of conditions that promote change.

- Through assessment, educators meet responsibilities to students and to the public.

This handbook is intended to provide program officers with the structure, guidance, and information they need to lead the practice of assessment within their programs.

[1] EDUC 289S course syllabus

[2] Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, Commission on Colleges

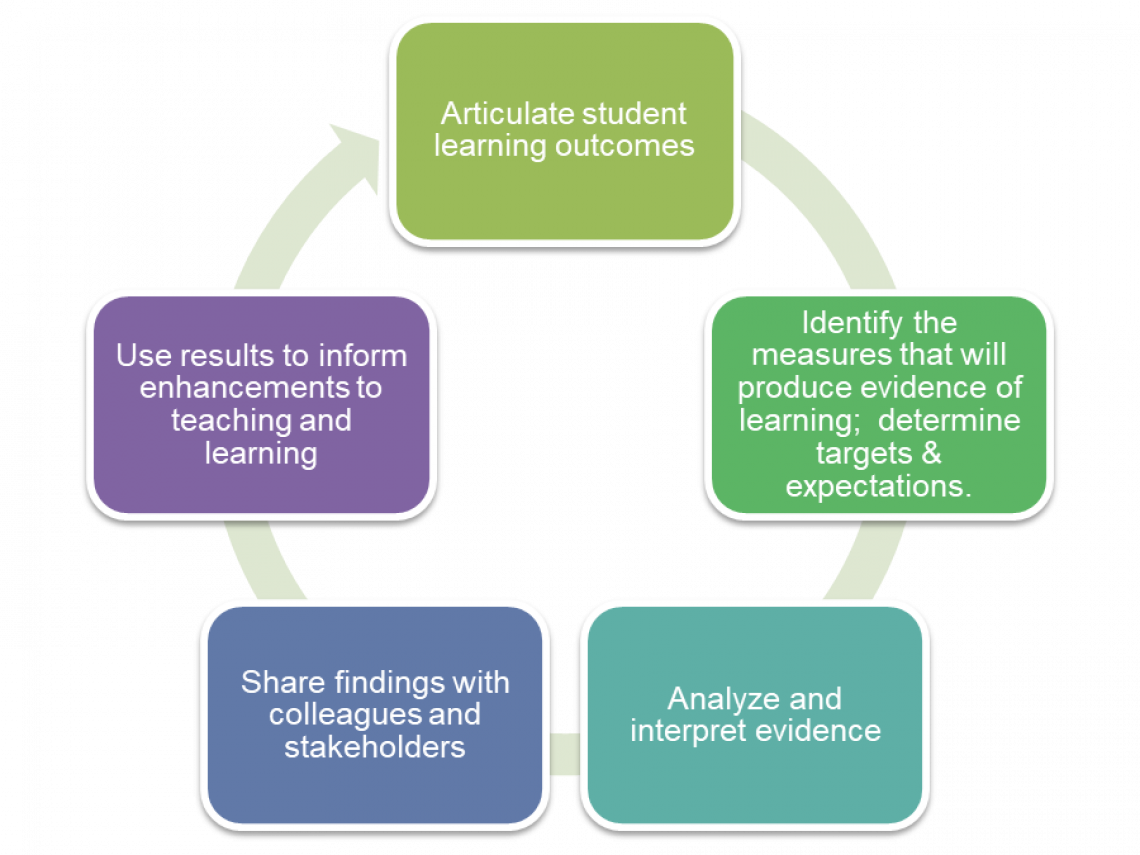

If one were to search for the term assessment cycle on the internet, the number of illustrations of assessment would be almost limitless. The descriptive vocabulary may vary from institution to institution, but these models share some central elements.

The Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP), which is described in detail in this document, guides faculty and program officers through this process.

First, the faculty within program must determine its learning outcomes: specific and measurable statements of what students know and are able to do by virtue of their participation in that program.

Second, the program must select or design the measures (or methods) by which it will collect information about the learning outcomes. It’s often necessary to use multiple measures, both direct and indirect, to understand whether and to what degree students are developing in these areas.

Third, once the data are in, faculty representatives begin the process of analyzing and interpreting them. This includes comparing the results with the program’s expectations.

Fourth, the individuals leading the collection and interpretation of evidence must share their findings with the larger faculty body.

Fifth, the program’s faculty determines how to use these findings to shape future enhancements to faculty teaching and student learning in the program.

The Office of University Assessment strives for common, accessible language to describe the study of teaching and learning. Some key terms, however, commonly appear in written publications on assessment and in conversations among practitioners of assessment.

Action research. Action research[1] commonly is understood as research intended to address an immediate issue, as well as the iterative process of problem-solving among individuals engaged in communities of practice. Linda Suskie provides a helpful contrast between traditional empirical research and assessment:

“[the former] is conducted to test theories, while assessment… [is] a distinct form of action research, a distinct type of research whose purpose is to inform and improve one’s own practice, rather than make broad generalizations… It is disciplined and systematic and uses many of the methodologies of traditional research… [Practitioners] aim to keep the benefits of assessment in proportion to the time and resources devoted to them.”[2]

Authentic evidence. Authentic assessments sometimes are called “performance assessment.” In contrast to traditional assessments (e.g., multiple choice tests), authentic assessments like writing assignments, projects, lab activities, computer programs, and portfolios, among others enable students to demonstrate students’ skill, competency, and ability in real world situations. The evidence derived from these measures may be described as “authentic evidence.”

Benchmarks. It would be difficult to interpret the results of one’s assessment activities without a standard against which to compare those results. As one begins planning and implementing an assessment task, it is helpful to articulate that standard. The Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP) refers to benchmarks as “targets”. The following table[3] introduces some of the benchmarks commonly recommended and used by the Office of University Assessment.

|

Benchmark |

Questions the benchmark can answer |

|

Local standards |

Are our students meeting our own standards or expectations? |

|

External standards |

Are our students meeting standards or expectations set by someone else? |

|

Internal peer benchmark |

How do our students compare to peers within our course, program, or college? |

|

External peer benchmark |

How do our students compare to peers at other colleges? |

|

Value-added benchmark |

Are our students improving over time? |

The selection of an appropriate benchmark depends on the availability of comparative information, whether from past studies, internally within the institution, or externally across institutions. In all cases, it is useful to develop a consensus among faculty so that, eventually, the findings will be accepted and acted upon by specific stakeholders.

Closing the loop. . Perhaps the single most important part of assessment is using one’s findings to influence or make changes to student learning experiences. If a program’s targets are not met, the faculty should consider why and what to do about it. But even when targets are met, one can still using these findings to guide discussion about the state of the curriculum, advising, resources, the assessment plan itself, and so on. In many cases, adjustments are small scale and straightforward to administer. In other cases, the suggested changes may require months or a year, over sequential steps of implementation. The Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP) walks one through the process of interpreting findings and make decisions about next steps.

Curriculum map. A curriculum map[4],[5] is a planning and organizational device in which the practitioner aligns the student learning outcomes with different points in the students’ learning experience. It encourages discussions among faculty about when students are expected encounter, develop, and master essential learning outcomes. It exposes and enables a critical review of possible misalignments. Finally, it helps individuals plan for the most suitable times to collect evidence of learning from students, and from which learning tasks.

Direct and indirect measures. There are many ways to characterize or differentiate assessment measures. Direct measures are those that show in a clear, tangible, and compelling way what students know and can do. These include performances, presentations, written work, capstone projects, and mentor or employer observations. Usually these demonstrations of ability are rated by faculty reviewers, using a rubric. By contrast, indirect measures approximate what students know and can do. Suskie explains, “indirect evidence consists of proxy signs that students are probably learning”.[6] Surveys and course evaluations are indirect measures: in most cases they ask students to self-report their perceived learning progress. Other examples include course grades, retention and graduation rates, placement rates, participation in learning experiences, and awards received. It’s worth noting that grades usually are treated as indirect measures because often it is difficult to reliably deconstruct how the grade maps onto or is aligned with the learning outcomes of the course or program.

Experiential learning. The Association for Experiential Education explains it as “a philosophy that informs many methodologies in which educators purposefully engage with learners in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people's capacity to contribute to their communities.”[7] Recognized by the Association of American Colleges and Universities [AACU] as a high-impact practice[8], experiential learning connects classroom-based learning activities with real world contexts and problems. The Office of Civic Engagement[9], DukeEngage[10], and Service-Learning[11], are examples of Duke programs providing connecting students and faculty to structured opportunities for experiential learning.

Formative and summative assessment. Formative assessment generally refers to the learning process: how does one provide feedback to students to facilitate the process of learning and development? Such assessments happen while the course (or other learning experience) is underway, and they are used to improve or enhance the learning of current students by making in-time adjustments to the pedagogy or learning environment. Summative assessment, by contrast, occurs at the end of the learning experience, where we take stock of students learning across the experience. Formative and summative assessments are equally important and compatible.

High-impact practices. A handful of well-established teaching and learning practices are known to be beneficial for college students from many backgrounds, especially historically underserved students, who often do not have equitable access to high-impact learning.[12] These practices include:

|

First-Year Experiences Common Intellectual Experiences Learning Communities Writing-Intensive Courses Collaborative Assignments and Projects Undergraduate Research |

Diversity/Global Learning Portfolios Service Learning, Community-Based Learning Internships Capstone Courses and Projects |

Longitudinal and cross-sectional designs. Like many other research areas, assessment tries to understand gains made by groups of individuals over time. In that respect, this longitudinal approach is similar to a time-series design in which levels of competency (or skill, disposition, etc.) are measured at multiple points in time. This approach requires monitoring individuals over time and, in many cases, managing attrition in a study sample. Despite the analytic value of a longitudinal design, sometimes its logistical challenges compel the analyst to use a cross-sectional design. Instead of measuring learning gains in a student group over time, one might have data from a single point in time. To interpret data from a single point in time, however, the analyst must determine a suitable benchmark for comparison. (See section on benchmarks above.) Both approaches are useful for studying student learning, and they can be used in a complementary way.

Measures. A measure is a source of evidence. We use it as a noun, to indicate the device, tool, or mechanism through which we will collect information about student learning. Measures include student surveys, interviews, faculty-evaluated papers, among many others. A helpful list of measures is available on the Cleveland State University website.[13] his website also is linked from within the Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP) for easier reference.

Mission statement. All Duke University academic departments and programs should have codified mission statements on the program website. The mission statement, as an aspirational declaration of the core values of the program, should anchor the program’s student learning outcomes. One should observe clear alignment between the mission of the program and the student learning outcomes under exploration in the program’s assessment plan.

Program objectives. We understand that academic departments and programs measure a variety of things germane to undergraduate teaching and learning. Assessment, as it is commonly understood, focuses on understanding what and how students learn. Program objectives illustrate how the program itself wants to evolve. They may include tracking enrollment statistics, growing the number of faculty lines, promoting undergraduate research, and expanding laboratory space. These all are critical inputs to student learning, but they are not measures of learning. The Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP) provides you a space to document and share this important work but take care not to confuse program objectives and program evaluation with the genuine assessment of student learning.

Program review, program evaluation, and institutional effectiveness. Assessment, program review, evaluation, and institutional effectiveness often are used interchangeably, but inappropriately so. Linda Suskie attempts to clarify the difference:

Program review is a comprehensive evaluation of an academic program that is designed both to foster improvement and demonstrate accountability. [They include] self-study conducted by the program’s faculty and staff, a visit by one or more external reviewers, and recommendations for improvement… Student learning assessment should be a primary component of the program review process.[14]

She goes on to describe institutional effectiveness as promoting not only students learning, but also each of the other college wise aims [e.g., research and scholarship, diversity, community service]. Program review, evaluation, and institutional effectiveness represent broad efforts to demonstrate how well the institution is achieving its mission and core values. Learning outcomes assessment is a key part of those efforts[ADP1] .

Quantitative and Qualitative traditions of inquiry. Quantitative assessments generally include assessment that use structured, pre-set response options that are numerically coded for later analysis through descriptive or inferential statistical techniques. Qualitative assessments, on the other hand, use more flexible and naturalistic methods to identify themes and patterns.

Individuals who are new to the process of assessment understandably might assume that they are expected to produce numbers: correlation coefficients, inferential statistical models, etc. Not true! Our faculty partners are encouraged to develop assessments of learning that are aligned with and authentic to the research traditions of their disciplines. For example: a well-designed and carefully implemented set of focus groups, whose transcripts are rigorously coded and evaluated by a trained analyst can yield important, even transformative information about student learning. We encourage our partners to recognize and be open to the variety of assessment measures that can reveal insights about student learning.

Rubrics. Simply-put, rubrics are scoring guides. They guide raters through the criteria that represent levels of learning or competency. Their benefits include:

- They can clarify vague or undefined objectives.

- They help students understand the instructor’s or program’s expectations.

- They give students structure for self-evaluation and improvement.

- They help make scoring more consistent, reliable, and valid.

- They improve the quality of feedback and reduce disagreements with students.

Rubrics can take many forms, including almost limitless content. Thus, a rubric that is reliable, valid, and usable among multiple raters take time and practice to develop. Often it is helpful to pilot test a rubric before deploying it on a large-scale. For excellent examples of rubrics on a variety of competency areas, see the AACU VALUE Project.[15] They are free to the public, and open for local adaptation.

Student Learning Outcome [SLO]. A student learning outcome represents a destination: what do students know and what are they able to do by virtue of a learning experience? What are the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and habits of mind that students develop as a result of a program, class, or major? If these do not already exist for your program, you will need to reach consensus on these outcomes with all stakeholders and across all curricular offerings. [ADP2]

Program officers often need assistance developing and adapting student learning outcomes. A simple mnemonic is A + B + C: An actor undertakes or demonstrates a behavior in some learning context. For example, by graduation students in the Business major are able evaluate multiple sources of data to craft a hypothesis. The student learning outcome focuses on the resulting competency or skill, not on the inputs to or process of learning. Continuing the example above, the term paper requirement is not the outcome, it is the process by which students get to their outcome. Writing sound learning outcomes is a critical early step in the process of assessment planning. The measures one selects, the targets one sets, and one’s interpretation of evidence depend on the language of the student learning outcome.

Targets. See benchmarks, above.

Triangulation. One of the principles of action research is the necessity of triangulation. Student learning is messy and complicated. Given the myriad factors that influence learning (student, organizational, institutional) it can be very difficult to establish causality. As much as possible, we use multiple measures to paint a multi-dimensional picture of student learning. These sources of evidence ideally corroborate one another and reinforce the conclusion that students, indeed, have learned what you expect them to.

[1] Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Sage.

[2] Suskie, L. (2018). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. John Wiley & Sons. See page 15.

[3] Suskie, L. (2018). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. John Wiley & Sons. See table 15.1 on page 234.

[6] Suskie, L. (2018). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. John Wiley & Sons. See page 20.

[12] Derived from: https://www.aacu.org/resources/high-impact-practices

[14] Suskie, L. (2018). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. John Wiley & Sons.

Academic departments have some autonomy in their organization of officers’ roles and responsibilities. In many departments the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) and Director of Graduate Studies (DGS) assume responsibility for assessment operations. Other departments appoint an assessment liaison to coordinate assessment planning and implementation within and on behalf of the department, including the reporting of findings and proposed next steps for the development of the curriculum, course content, pedagogy, and academic support services. Still other department appoint a faculty committee to coordinate assessment of student learning.

The practical execution of roles naturally varies from program to program. The Department Chair or Program Director should create the organizational structure in which assessment occurs and provide appropriate direction.

Staff are critical participants in a well-functioning an academic unit. In addition to their operational expertise and knowledge of university systems, staff have close relationships across the faculty and student communities. Their partnership is invaluable, however, faculty bear final responsibility for the development and execution of learning outcomes assessment.

|

|

Chair[1] |

DUS, DGS, Assessment liaison, and/or faculty assessment committee |

|

Vision |

Oversees self-evaluation activities within the program. |

Leads the development and yearly review of learning outcomes for the educational experience. |

|

Assigning of responsibilities |

Determines which persons are responsible for the development, continuation, and evolution of the assessment plan and its implementation. |

Seeks assistance and collaboration from faculty colleagues. |

|

Implementation |

Provides leadership support to the assessment liaison |

Executes the planned assessment strategy with support from Chair, DUS, staff, and other faculty |

|

Communication |

Plans structured opportunities for the assessment liaison to share updates with the faculty and solicit feedback. |

Initiates conversations about student learning and assessment with faculty colleagues. Informs the program of institutional requirements regarding learning assessment. Liaise with the Office of University Assessment. |

|

Reporting |

Authors an annual report which articulates planning goals and objectives, and reports recent activities and outcomes. |

Completes the annual Department Assessment Portfolio by June 1 of each academic year. |

|

Data collection & analysis |

Provides leadership support to the assessment liaison. |

Structures and executes the collection and analysis, delegating to or collaborating with colleagues as appropriate to study learning in the program generally. |

|

Future planning |

Leads the effort to use findings to enhance student learning. |

Provides evidence-based recommendations to the faculty community to enhance undergraduate student learning generally. |

|

Resources |

Identifies needs and seeks resources (e.g., funding) |

Consults regularly with Office of University Assessment for support and guidance. |

The Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP) is the tool through which Trinity College academic programs plan for, describe, and document their study of undergraduate student learning. It is intended to be used throughout the academic year, reaching completion in late May. On June 1 of each academic year the Office of University Assessment will begin reviewing and providing feedback on each program’s portfolio. Program officers should expect notification of feedback in August, in preparation for the start of the next academic year.

Early in each academic year, the assessment liaison and/or Chair should meet with the program’s assigned assessment staff member to (a) begin the assessment process for the year and (b) to ensure access to and discuss any recent updates to the DAP. Instructional materials[1] are available for help and guidance.

The DAP requires the following pieces of information. At minimum, assessment liaisons should discuss these topics with the program Chair, DUS, and curricular liaison but preferably they should be informed and developed through wider conversations among program faculty.

- Mission statement for the program

- Explanation of the assignment and sharing of assessment responsibilities within the program

- Explanation of the implementation of planned actions from the previous assessment cycle.

- Evidence of an assessment plan and a proposal to improve the experience of undergraduate students in the first two years.

- Articulation of Student Learning Outcomes [SLOs].

Because the crafting of the SLO is a key part of assessment planning, the Office of University Assessment evaluates them carefully early in each assessment cycle. We also offer workshops, both live or recorded, to assist with the development of SLOs. [2] - For each of the 2-4 SLOs under exploration each year, the program describes:

- The measure(s) by which evidence about this SLO is collected

- The target: what it hopes to find

- The actual findings, and a judgment as to whether the SLO was met

- A general interpretative summary of the assessment findings for that outcome, across measures

- A plan for changes or enhancements, which may include updates to courses, course sequencing, advising practice, physical resources, or the assessment plan itself.

While the content of departments’ assessment plans vary widely, Trinity College nonetheless holds departments to the common standards of assessment practice. The rubric we use to identify points of strength/concern, guide our feedback, and report a general summary to College leadership is listed below; it was originally developed and deployed by the former Arts & Sciences Faculty Assessment Committee [ASFAC]. We use the numerical ratings to monitor aggregate progress over time and to identify areas needing focused support across the College in the present.

|

|

Not sufficient |

Can be improved |

Satisfactory (Meets expectations) |

||

|

1 pt |

2 pts |

3 pts |

4 pts |

5 pts |

|

|

1: The department clearly identifies its mission & goals. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2: The department clearly identifies specific learning objectives/ outcomes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3: The department clearly identifies measures, instruments, and indicators. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4: The department clearly identifies the methods and standards used to judge the quality of learning products and indicators. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5: Achievement targets are clearly identified. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6: Findings are discussed in the assessment report; the report indicates if targets have been met. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7: Findings are shared and discussed with faculty members in the department for purposes of future target setting and action planning; faculty members engage in meaningful discussion about the assessment. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8: The department takes specific actions (based on findings) to strengthen undergraduate education. The department sets clear future targets. |

|

|

|

|

|

Written feedback from Assessment personnel is compiled each summer during the review process, and the feedback is released to all departments concurrently at the end of the summer. Chairs and Directors of Undergraduate Study may request the feedback from their assessment liaisons at any time.

[1] https://assessment.trinity.duke.edu/program-assessment/starting-the-DAP

[2] https://assessment.trinity.duke.edu/assessment-roundtable#fall2017

The Office of University Assessment administers course evaluations on behalf of Trinity College academic departments and other schools. The questionnaire rarely is revised at the request of and in partnership with the Provost’s Office, and we inform program officers by email as soon as the updates are finalized. General instructions for academic departments and programs[1],[2] are available online, and are distributed by email each term prior to the opening of the course evaluation window. Student questionnaires and associated “codebooks” also are available on our website.[3]

In general, we evaluate all Trinity College courses excluding the following course components: Independent Study, Practicum, Preceptorial, and Recitation. Any further removals or customizations of courses or sections can be made by authorized departmental personnel during the departmental window. Courses with eligible components will automatically be included in the initial lists for evaluation; however, if evaluated, results for courses with less than five (5) enrollments will be restricted from instructor view. Departments will have access to the results of all small courses for interpretation and feedback, which they may share at their discretion.

Schedule

The schedule for undergraduate course evaluation administration is reflective of course end dates. Evaluations for students open 10 days before the last day of class and close 3 days after the individual course end date. Window dates will vary by term as the official university calendar shifts.[4] Please watch for informational emails from the Office of University Assessment explaining relevant dates and deadlines for the present term.

Responsibilities of the Academic Program

An email outlining the timeline and process of program level responsibilities for the evaluation cycle is sent out each semester. At the request of the Office of University Assessment, department personnel review the final list of courses to be evaluated each term. Department personnel bear no responsibility for the dissemination of questionnaires to students. Students may access evaluations via DukeHub, as well as notification emails from the office of the Dean of Academic Affairs with direct links to the evaluation system. In addition to the email communications, instructors are strongly urged to explain the value of course evaluations to students during each evaluation window; please reiterate this point to your faculty colleagues. Recommendations to faculty are shared via email. In the interest of monitoring and providing effective feedback about teaching and learning, department Chairs and DUSs are expected to access course evaluation reports regularly.

Reports

Course evaluation data can and should be used to inform teaching and planning. After the evaluation cycle, reports are made available within Watermark, the same tool used for evaluation. Authorized users have the ability to download results to answer important questions about your course(s) or academic department(s). Instructions for navigating reports in Watermark, as well as managing user access and viewing APT-specific reporting in Tableau are all available on our website. [5]

SACES

Active Duke students may access the Student Accessible Course Evaluation System (SACES) reports to view the course evaluation results for select courses. Access to search course results is available through the 'Additional Links' section of a course listing in DukeHub. Instructors who chose to opt-out of the SACES system will not appear in these tables.

Some faculty may recall the now-obsolete Instructor Course Description Form, often called the “faculty form”. This questionnaire asked instructors to provide information about the course pedagogy and expectations, in addition to the instructor’s decision to release course evaluation results to students (“opt-in”) or to keep them private (“opt-out”). In the absence of this questionnaire, faculty now indicate their opt-out preference on a Qualtrics web form, which is shared with the release of evaluation results at the end of each term

SACES reports are not updated in real-time. Assessment personnel update the reports each semester, before the opening of shopping carts for the following term.

Appointments, Promotion, and Tenure (APT)

Several tables within the program’s course evaluation reports are required for the APT process. Individuals completing the course evaluation section of a dossier are encouraged to contact Faculty Affairs for guidance.[6]

Supplemental Evaluations of Teaching and Learning

We are pleased to share that the capability for custom questions is available at the department and instructor level in Watermark. Each term, departments and instructors are notified when their respective window for adding custom questions is open, and instructional materials are available on our website. [7]

Many faculty wish to collect additional information about student learning, often at a mid point in the term. Trinity College does not have a formal, universal process for mid-semester evaluations, but we have cultivated a handful of online resources and recommendations to guide faculty through this process.[8]

[1] https://registrar.duke.edu/faculty-staff-resources/course-evaluations/course-list-review/

[2] https://registrar.duke.edu/faculty-staff-resources/course-evaluations/custom-questions-guide/

[3] https://registrar.duke.edu/faculty-staff-resources/course-evaluations/questionnaires/

[4] https://registrar.duke.edu/faculty-staff-resources/course-evaluations/calendar/

[5] https://registrar.duke.edu/faculty-staff-resources/course-evaluations/reports/

[6] https://admin.trinity.duke.edu/faculty-affairs/policy/course-evaluation-tabular-summaries

[7] https://registrar.duke.edu/faculty-staff-resources/course-evaluations/custom-questions-guide/

[8] https://assessment.trinity.duke.edu/midterm-assessment-strategies

Course evaluations are not the only report type published in Tableau. We publish other information on the students graduating from your major, minor, and/or affiliated certificate program in the Program-level reports (student information) dashboard. The purpose of this canon of reports is to help you understand which students your program has served in the major, minor, and/or certificate, what these students do during their time at Duke, and perhaps most importantly, how they score on Trinity College’s assessment of key competencies in the general education.

To elaborate on this last point, the College issues a handful of assessment to new first-year students in the summer before Orientation. Of the approximately 1700 new matriculates, one-third are asked to complete a test of ethical reasoning, one-third are asked to complete a test of global perspectives and engagement, and one-third are asked to complete a test of quantitative literacy and reasoning. Participation is voluntary, and the tests are completed online before August Orientation. In addition, a test of critical thinking is administered to a voluntary sample of students after their arrival on campus, shortly after the end of the add/drop period. This is a proctored test, which cannot be administered online.

The results of these tests become a baseline measure for these competencies at matriculation. Student participants are asked to re-take the same assessment in their senior year, roughly February – March, to help us determine whether and to what degree students have developed in each of these competency areas. We understand that many factors influence students’ performance on these measures, and that they are best interpreted in conjunction with other sources of evidence.

Although these data originally were intended for the assessment of the Trinity College general education – and continue to be used in this way – it also makes sense to provide relevant subsets of the data to program officers as well. When you log into the Tableau reports, your credentials will determine which cases you are permitted to see: specifically, students who graduated with a major, minor, and/or affiliated certificate in your program. Login here: http://bit.ly/program_dashboard

The Office of Assessment developed a simplified dashboard, Enhancing Undergraduate Teaching and Learning, that provides data for each department about which students are taking your courses, the quality of teaching in your courses, and grade distributions. These are streamlined reports help to answer questions pertaining to the first two years of an undergraduate student’s Duke experience, such as:

- What is the student experience with the introduction to your field?

- If your introductory courses are the only ones that a student takes in your field, then is it the experience that you would want them to have?

- How do your introductory courses create a climate of inclusion and belonging?

- If a student takes an introductory or service course in your discipline,

- does it engage that student so that the student sees its importance and relevance?

- does it stimulate a student intellectually so that the student’s intellectual capacities are deepened and broadened?

These dashboards should be read and utilized in conjunction with other information about student learning in your program. Your contact in the Office of Assessment can help you make sense of and use these data sources effectively.

The following institutes, programs, and offices support the work of assessment, both directly and indirectly, and often provide guidance for individuals studying the process of teaching and learning. Several are described elsewhere in this document

|

Social Science Research Institute [SSRI] |

|

|

Office of the University Registrar |

|

|

Office of Institutional Research |

|

|

Learning Innovations, formerly the Center for Instructional Technology |

|

|

Provost’s Office of Faculty Affairs |

|

|

Office of Research Support, and the Duke Institutional Review Board |

|

|

Data and Visualization Services (Duke Libraries) |

|

|

Division of Student Affairs: Assessment & Research |

https://students.duke.edu/sa-intranet/departments-units/assessment/ |

Chair

- Confirm that you can access reports for course evaluations and information about students affiliated with your program.

- Determine who needs access to departmental data.

- Make sure that the designated staff member in your department checks and approves the list of courses that require evaluation each term. Watch for emails email from the Office of University Assessment .

- Confirm with assessment personnel that we have you on our list of Chairs, and that your email has been added to our listserv

- Support and encourage the assessment efforts of the assessment and curricular liaisons

Director of Undergraduate Studies and/or Assessment Liaison

- Connect with the Office of University Assessment to schedule an initial one-on-one consultation to discuss plans for the assessment of teaching and learning in your program.

- Make sure you have the current version of the Department Assessment Portfolio.

- Obtain and review assessment feedback from the previous year’s Department Assessment Portfolio (DAP).

- Obtain a copy of the program’s assessment plan from your predecessor, if applicable.

- Review and understand your program’s current Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs). Prepare to discuss them with faculty colleagues.

- Confirm with assessment personnel that we have you on our list of DUSes/Liaisons, and that your email has been added to our listserv.

- Schedule a meeting with a member of the assessment team early in each academic year to coordinate and communicate assessment efforts for the coming year.

The Office of University Assessment maintains a comprehensive list of relevant informational resources on our website.[1] These include well-regarded national and regional organizations that lead and support best practices in assessment, as well as individual institutions and programs that provide quality examples of a variety of assessment activities and methodologies. A brief bibliography of important scholarship in the field of assessment is listed below.

Cambridge, D., Cambridge, B. L., & Yancey, K. B. (Eds.). (2009). Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Ewell, P. T. (2002). An emerging scholarship: A brief history of assessment. Building a scholarship of assessment, 3-25.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). Excerpt from high-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Kuh, G. D., Jankowski, N., Ikenberry, S. O., & Kinzie, J. L. (2014). Knowing what students know and can do: The current state of student learning outcomes assessment in US colleges and universities. Urbana, IL: National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Maki, P. L. (2012). Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Palomba, C. A., & Banta, T. W. (1999). Assessment Essentials: Planning, Implementing, and Improving Assessment in Higher Education. Higher and Adult Education Series. Jossey-Bass.

Suskie, L. (2018). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. John Wiley & Sons.

Walvoord, B. E. (2010). Assessment clear and simple: A practical guide for institutions, departments, and general education. John Wiley & Sons.

External Web Resources

|

Association of American Colleges & Universities [AACU] |

|

|

Liberal Education & America’s Promise [LEAP] Initiative |

|

|

Valid Assessment Learning in Undergraduate Education [VALUE] Project |

|

|

Project Kaleidoscope [PKAL] |

|

|

Association for Authentic, Experiential, and Evidence-Based Learning [AAEEBL] |

|

|

National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment [NILOA] |

|

|

Consortium on the Financing of Higher Education [COFHE] |

|

|

Teagle Foundation |

|

|

Spencer Foundation |

|

|

Lumina Foundation |